Book Review: The Anatomy of Greatness - Brandel Chamblee

Click here to go back to the home page.

Introduction:

This review paper represents a critical review of the opinions expressed by

Brandel Chamblee in his book called "The Anatomy of Greatness" [1]. Brandel

Chamblee is presently a reknown (albet controversial) Golf TV commentator on the

Golf Channel, and he previously played golf as a professional golfer on the PGA

tour for a 15-year time period. In his book, Brandel Chamblee posted the

following comments in the "About Brandel Chamblee" section of his book-: "Chamblee

has earned a reputation for being one of the most intellectual, accurate,

insightful, and well-researched personalities on Golf Channel. He is known for

his keen knowledge of the golf swing and the history of the game." Based on

those statements, Brandel Chamblee obviously believes that he has great insight

into the mechanics/biomechanics of a well-executed full golf swing and he

harbors strong opinions on what represents the optimum way to perform a full

golf swing. Brandel Chamblee seemingly believes that many modern day golf

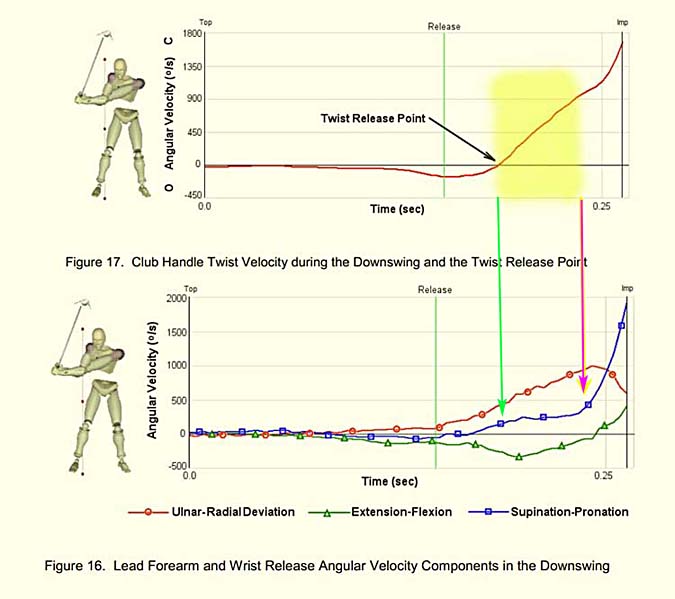

instructors are not teaching the optimum way to perform a full golf swing, and

he seemingly thinks that they have lost their way. He apparently believes that

present day golf instructors should go back to teaching the swing elements

manifested by many great golfers from a bygone era (like Bobby Jones, Sam Snead,

Ben Hogan, Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Mickey Wright) and he provides many

examples of swing elements that he believes are very desirable. I have no

problem with the "fact" that he harbors strong personal choices when it comes to

desirable swing elements, but he seemingly adopts the radical position that his

personal choices have been proven to be better than the swing elements adopted

by many modern day professional golfers (such as Adam Scott, Jordan Spieth, Rory

McIlroy and Jason Day). I believe that he is wrong about many of his personal

choices - either in terms of their fundamental "essentiality" with respect to a

well-executed full golf swing or with respect to his personal explanations about

the underlying golf swing biomechanics that underpin those swing elements. In

this review paper, I will thoroughly dissect his opinions and provide my

personal (and often contrary) opinions, so that readers of this critical review

paper can independently judge the merits of our respective opinions. I will

basically follow the pattern of chapters as they were presented in Brandel

Chamblee's book in this critical review paper, and I will

mainly comment on swing elements where Brandel Chamblee and I harbor very

different opinions.

Chapter 1 - The Grip

Brandel Chamblee made the following statement in his book-: "Among amateurs there is often some confusion and much error when it comes to placing their hands on the club. I believe much of the problem is rooted in the most popular instruction book ever written." The book that he is referring to is Ben Hogan's "Five Lessons" golf instructional book, and he quoted from the book as follows-: "On page 26 of Five Lessons: The Modern Fundamentals of Golf, Ben Hogan states that, when placing your left hand on the club, the V formed by the marriage of the index finger and the thumb (for a right-handed golfer) should point to the right eye. On page 28 he states that the V formed by the index finger and thumb of the right hand should point to the chin. In professional golf-speak, this is known as a weak grip. Hogan’s was one of the most beautiful the game has ever seen. ---- It was beautiful because he crooked his right index finger, which he called a trigger finger, back just enough to where he could push the top joint into the side of the grip and apply pressure and this cohesiveness, between index finger and thumb, gave his grip an almost unmatched symmetry." However, although Brandel Chamblee describes Ben Hogan's left hand grip as being "beautiful", he also believes that a weak left hand grip will predispose to an open clubface at impact if the clubshaft has forward shaft lean - unless the golfer uses some compensatory maneuver (eg. increased left forearm supination). Brandel Chamblee therefore concludes that a golfer should use a stronger left hand grip, and he states in his book-:"As beautiful as Ben’s grip was, it was unique to him. The vast majority of great players have used a much stronger grip, and most amateurs should, too. A stronger grip is the grip of choice— the commonality among the best in the game— and the easiest path to improvement.

Brandel Chamblee then describes how a golfer should adopt a stronger left hand grip as follows-: "In placing the left hand on the club, the grip should run diagonally from the lower part of the palm, specifically right on the thickest crease in your palm, known as the Line of Heart, across the top joint of your middle two fingers and lay on the middle joint of your index finger. Then the thumb is folded over and placed just to the right of the center of the club. The V formed by the thumb and index finger should point toward the right shoulder. If yours points toward your chin or right eye, keep turning it clockwise until it approximates the greats. --- If one takes up the grip too much in the palm or with the thumb straight down the club, at the top of the swing the hand and thumb will likely not be in position to support the weight of the club and the stress of the transition. Hence, the club should be placed diagonally in the hand, with the thumb on the side of the shaft. The placement of the left hand has a very distinct purpose. The left hand provides the stability in the strike but the full range of motion should never be compromised. The tendency is to take up the grip completely in the palm, but this is disastrous, as the player will lose some range of motion in the wrist and security of the club at the top of the swing."

What Brandel Chamblee is basically describing is a low palmar grip of neutral-to-slightly strong strength (2-3 knuckle left hand grip).

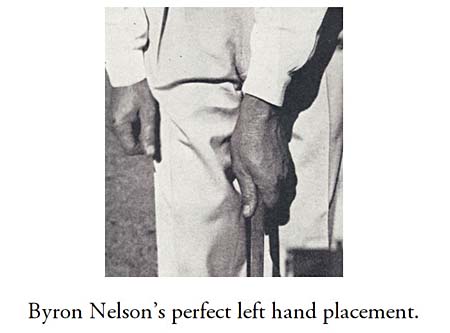

Brandel Chamblee uses the following image of Byron Nelson's left hand grip as a prototypical example of perfect left hand grip placement.

Image copied from reference number [1]

I have no objection to his personal choice of that pattern of left hand grip, which is a very common choice among skilled professional golfers, but I think that his reasoning for choosing a stronger left hand grip and his description of how best to adopt a slightly strong left hand grip is flawed.

Consider the "idea" of using the V-direction as the optimum method of adopting a stronger left hand grip.

Note that Byron Nelson chooses to have his clubshaft perpendicular to the ball-target line at address so that his hands are no closer to the target than his clubhead, which means that he has to disrupt his intact LAFW (defined as a clubshaft that is straight-in-line with the left arm) by bending his left wrist. Under those conditions (with the hands midway between the thighs), the V formed by the left thumb and left index finger will likely point at the right shoulder at address.

However, some golfers prefer to have their left arm and clubshaft straight-in-line (and with forward shaft lean) at address, and that personal choice will affect the direction that the V will point at address.

Consider an example of that personal choice - Dustin Johnson.

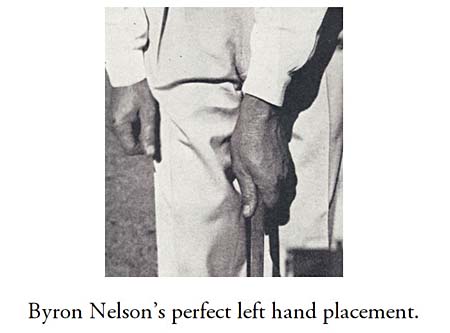

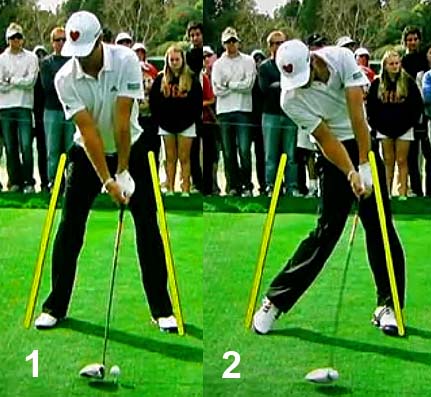

Image 1 shows Dustin Johnson at address, while image 2 shows him at impact.

Note that Dustin Johnson has his clubshaft straight-in-line with his left arm at address, which means that his left wrist is not bent - even though it may "appear" to be bent in that image. However, the "real" reason why his left wrist is dorsiflexed at address is due to the "fact" that he adopts a moderately strong (3-knuckle) left hand grip with his left thumb placed on the aft side of the grip handle. Note that the V formed between his left thumb and left index finger points at his chin, and not at his right shoulder, at address - even though he has adopted a moderately strong left hand grip. That's why one should not assess the strength of a golfer's left hand grip at address using the V-direction technique - because of the additional biomechanical variable of hand position at address, and whether the golfer arbitrarily/preferentially decides to have a forward angulated shaft at address (like Dustin Johnson where his hands are closer to the target than his clubhead) or whether a golfer prefers to have the clubshaft perpendicular to the ball-target line at address with his hands not being closer to the target than the clubhead (like Byron Nelson).

I think that the optimal way for a golfer to establish his left hand grip strength is to make the determination when the left arm and clubshaft are in a straight line, with the left arm-clubshaft combo vertically aligned with respect to the left shoulder socket.

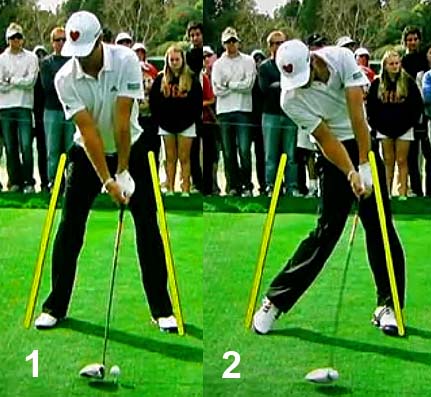

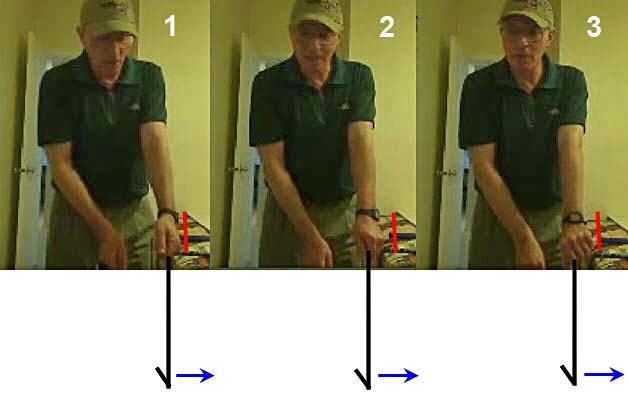

Consider my "method" of determining left hand grip strength.

Note that I have drawn in black an imaginary golf club that is straight-in-line

with my left arm in all three images, which means that the left wrist is

geometrically flat (the GFLW is represented by the short red line) in

all three images, and it also means that the LAFW (left arm flying wedge) is

intact. The clubface faces the target in all three images (represented by the

blue arrow). In image 1, I have adopted a weak (1-knuckle) left hand grip where

I have placed my left thumb at the 12 o'clock position on the grip - note that

the degree of cupping of the back of the left hand appears to be very small in

amount. In image 2, I have pronated my left forearm more (note that the

watchface over the dorsum of my left lower forearm has rotated more clockwise)

before I grip the handle of the club, and that causes my left thumb to be

positioned at the 1:30 o'clock position (when viewed from above) when I grip the

club. That represents a slightly strong (2-3 knuckle) left hand grip. Note that

my left wrist appears to be more cupped (dorsiflexed) - even though I

still have a geometrically flat left wrist. In image 3, I have adopted

a very strong (4+ knuckle) left hand grip by pronating my left hand even more so

that my watchface is nearly parallel to the inclined plane before I grip the club, and

that positions my left thumb at the 3 o'clock position (when viewed from above).

Note that the ulnar border of my left hand, and not the back of my left hand, faces the target. Under those

conditions, I still have a GFLW because the clubshaft is still in a straight

line relationship with the left arm. Therefore, it is important to realise that

the visual appearance of the back of the left wrist/hand in terms of its

degree of cupping (dorsiflexion) will vary depending on left hand grip

strength - when a golfer adopts a GFLW at address. Note that the clubface will

only appear to be roughly parallel to the back of the GFLW/lower left forearm

(watchface area) when the golfer adopts a weak left hand grip, and that it

appears to be more closed relative to the back of the GFLW/left lower forearm

(watchface area) when a golfer adopts a stronger left hand grip. So, for

example, if a golfer adopts a slightly strong (3-knuckle) left hand grip at

address, then the clubface will be closed by ~20-45 degrees (relative to the

back of the GFLW/left lower forearm (watchface area) at address and if he adopts

a very strong (4+ knuckle) left hand grip at address, then the clubface will be

closed by ~45-60 degrees (relative to the back of the GFLW/left lower forearm

(watchface area) at address. If that same golfer maintains a GLFW throughout his

backswing, downswing and early followthrough action, then the clubface will

always be closed relative to the back of his GFLW/left lower forearm (watchface

area) by exactly the same amount if he continuously maintains an intact

LAFW/GLFW alignment.

Now, consider Brandel Chamblee's reasoning when it comes to his personal left hand grip choice of a low palmar grip of moderate (2-3 knuckle) strength. First of all, he states in his book [1] that a golfer who uses a weak left hand grip strength will likely have an open clubface at impact because of the presence of forward shaft lean due to left wrist bowing and that the golfer will therefore need to use a compensatory maneuver (eg. increased left forearm supination) in order to achieve a square clubface at impact. I don't disagree with his reasoning, but he seemingly fails to understand that if a golfer (who adopts a moderately strong left hand grip - like Dustin Johnson) has forward shaft lean at impact due to a bowed left wrist, that he will also need to compensate by incorporating a greater degree of left forearm supination in order to achieve a square clubface at impact. The proof (regarding my claim) can easily be discerned by studying this composite image of Dustin Johnson at address and at impact.

Note that Dustin Johson has a square clubface at address (image 1) and at impact (image 2). Note that Dustin Johnson has an overtly bowed (slightly palmar flexed) left wrist at impact (which is associated with forward shaft lean where the hands are well ahead of the clubhead at impact). Using the radial border of his left radius bone (which is visually apparent in his left lower forearm just above the level of his glove) as a reference point, one can clearly see that his *left forearm is more supinated (relative to his left antecubital fossa) at impact (image 2) when compared to address (image 1).

(* If you are interested in more clearly undertanding why Dustin Johnson, who uses a moderately strong left hand grip, has to use more left forearm supination during his release of PA#3 in order to achieve a square clubface at impact when he has forward shaft lean at impact due to left wrist bowing/arching - see topic 3 in this review paper)

Now, consider another comment that Brandel Chamblee made with respect to the position of the club handle within the left hand when he stated-: "The placement of the left hand has a very distinct purpose. The left hand provides the stability in the strike but the full range of motion should never be compromised. The tendency is to take up the grip completely in the palm, but this is disastrous, as the player will lose some range of motion in the wrist and security of the club at the top of the swing."

The word "disastrous" is a very strong word to use when describing a golfer's choice to use a mid-palmar grip pattern (rather than a low palmar grip pattern or a finger grip pattern).

Consider a mid-palmar grip pattern (photo image derived from my grip chapter).

Note that the more proximal part of the grip goes directly over the hypothenar eminence

(over point C) rather than going over point N, which is just below the hypothenar eminence

(and which is characteristic of a low palmar grip pattern), or over point D

(which is characteristic of a finger

grip pattern). That mid-palmar grip pattern causes the grip to lie more diagnonally across the palm,

so that the clubshaft is more straight-in-line with the left arm,

which decreases the accumulator #3 angle. That mid palmar grip pattern is indeed

associated with restricted left wrist mobility (as Brandel Chamblee claims) and

I also previously believed that it was not suitable for a full golf swing.

However, I have recently revised my opinion after seeing how successfully Moe

Norman and Bryson DeChambeau have used that mid-palmar grip pattern for their full golf

swing action. Bryson DeChambeau can generate an average clubhead speed of 118mph

with his driver when using a mid-palmar left hand grip, which results in a

driving distance that is only ~30 yards shorter compared to the situation when

he uses a finger grip pattern (that allows for a greater degree of left wrist

mobility). He states that he achieves much better driving accuracy when using a

mid-palmar left hand grip (albeit at the cost of a potential loss of maximum

driving distance), which is very useful when faced with a "tight fairway"

scenario. He routinely uses the mid-palmar grip pattern for all

his irons (which are all of the same length and lie angle) in his zero-planar

shift swing action. I therefore now believe that adopting a mid-palmar grip pattern is a

very acceptable choice for a professional golfer who also wants to perform a

zero-planar shift swing action where the clubshaft descends down a steeper

planar path

(between the elbow plane and the TSP) and where there is a very small

accumulator #3 angle at impact.

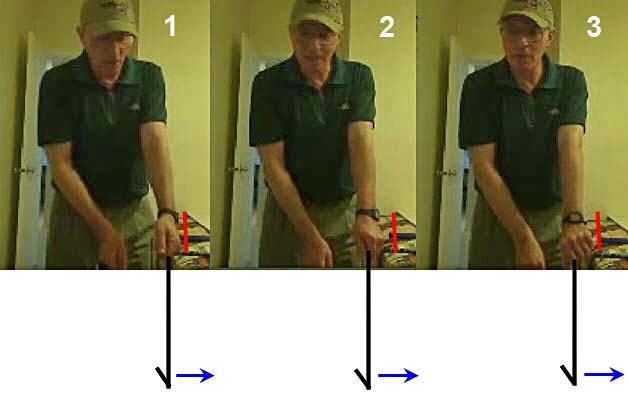

Consider Bryson DeChambeau's accumulator #3 angle at impact.

Image 1 shows Bryson DeChambeau at address, image 2 shows Bryson DeChambeau at

impact, and image 3 shows how one can measure the magnitude of the accumulator #3 angle at impact.

The accumulator #3 angle is actually the obtuse angle (wedge-shaped angle)

between the left arm and the clubshaft on the left thumb side of the club (upper

side of the club), and the magnitude of the accumulator #3 angle = 180 degrees

minus the obtuse angle. So, if the obtuse angle is close to 180 degrees, then a

golfer has a small accumulator #3 angle, and if the obtuse angle is closer to

120 degrees, then a golfer has a much larger accumulator #3 angle.

Note that Bryson's left arm and clubshaft are nearly in a straight line relationship at address and also at impact and he only has an accumulator #3 angle of ~10-13 degrees at impact. The magnitude of the accumulator #3 angle (in degrees) is equal to the angle between the red line drawn down the longitudinal axis of his left arm and his clubshaft.

The advantage of a smaller accumulator #3 angle is directly related to the "fact" that there will be less clubhead motion in space along the path of the clubhead arc for every 1 degree of supinatory roll of the left forearm during the release of PA#3, which happens between P6.5 and impact. That makes it theoretically easier for a golfer to more controllably achieve a square clubface by impact, and it is probably a major factor (in conjunction with a zero/near-zero planar shift pattern) that is causally responsible for Moe Norman's legendary ball flight accuracy.

Regarding the "security" of the grip in the left hand at the end-backswing position, I know of no reason why a mid-palmar grip pattern should be less secure than a a low palmar grip pattern - especially if a golfer uses custom-fitted Jumbo XL grips like Bryson DeChambeau.

Finally, it appears to me that the major reason why Brandel Chamblee prefers a slightly strong left hand grip (where the left thumb is placed at the 1:30 o'clock position on the aft side of the club) is based on his "belief" that it will likely position the left thumb under the handle of the club at the end-backswing position, and he believes that an under-the-club position of the left thumb will optimally support the weight of the club at the end-backswing position. Consider what Brandel Chamblee wrote in his book [1] when he stated-: "If one takes up the grip too much in the palm or with the thumb straight down the club, at the top of the swing the hand and thumb will likely not be in position to support the weight of the club and the stress of the transition." I personally think that it is a mistake to believe that the weight of the club should be primarily supported by the left thumb at the end-backswing position, because I think that the RFFW (right forearm flying wedge) should be correctly positioned at the end-backswing position in order to support the weight of the club at the end-backswing position.

Consider this composite image of Tiger Woods and Adam Scott at their end-backswing position.

Note that both Tiger Woods and Adam Scott have an intact LAFW (colored in yellow where the left arm and clubshaft have a straight-in-line alignment) and note that their intact LAFW/GFLW is parallel to the inclined plane. The RFFW (consisting of the right forearm and bent right wrist) is colored in red, and it is optimally positioned so that the right palm is parallel to the GFLW, which is itself positioned parallel to the inclined plane. The right palm is supporting the weight of the intact LAFW, and therefore the weight of the club, at the end-backswing position, and it doesn't really matter whether the left thumb is located precisely under the shaft (rather than being positioned to the side of the shaft).

Consider this capture image of Dustin Johnson at his end-backswing position.

Note that Dustin Johnson has a markedly bowed/arched left wrist at his

end-backswing position, which means that his left thumb cannot possibly be

located under the club at his end-backswing position. That "fact" doesn't matter

because his RFFW is optimally positioned so that his right palm is parallel to

the undersurface of his club, and his club's weight is being perfectly supported

by his optimally positioned RFFW.

In summary, I agree with Brandel Chamblee that a neutral-to-slightly strong left hand grip, using a low palmar grip pattern, is a very suitable choice for a golfer's left hand, but I am not as rigid as Brandel Chamblee and I believe that it is also perfectly accptable for a golfer to use a weak left hand grip (like Ben Hogan) or a very strong left hand grip (like Zach Johnson, Ryan Palmer, and David Duval). I also think that even though it is true that many professional golfers prefer to use a low palmar grip pattern, that it is very acceptable to use either a mid-palmar grip pattern (which offers better clubshaft control at the expense of wrist mobility) or a finger grip pattern (which offers more wrist mobility at the expense of clubshaft control).

I will not discuss issues related to the right hand grip because there is nothing controversial about Brandel Chamblee's opinions on the choice of a right hand grip pattern. He, like me, believes that the right hand grip pattern should be neutral (and not weak or very strong).

Chapter 2 - The Setup

Stance width

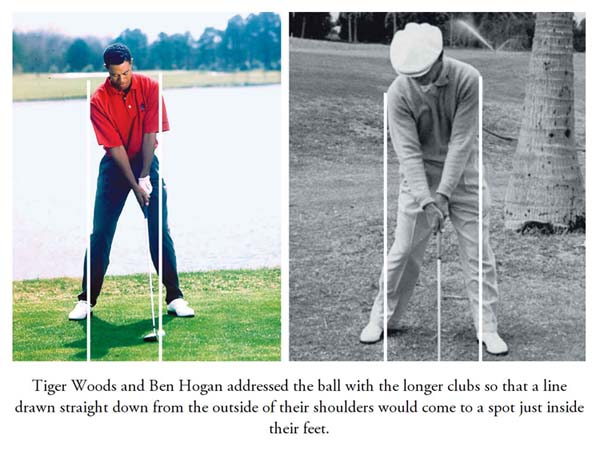

Brandel Chamblee prefers a slightly wide stance for a driver swing where the stance width is slightly wider than the width of the shoulders, and he uses these images of Tiger Woods and Ben Hogan to make his point.

Image copied from an image in reference number [1]

Brandel Chamblee states this stance width choice offers a good balance between

pelvic mobility versus stability, and I agree with his reasoning.

I also agree with Brandel Chamblee that it is very natural for the stance width to narrow when a golfer uses shorter irons.

Right knee

Brandel Chamblee made the following comment in his book [1]-: "Almost every great player kicked the right knee in to start the swing. Some, such as Gary Player and Mickey Wright, did it in a more pronounced fashion than others, but this kicking in of the right knee is one of the most important aspects in initiating the correct sequence of many movements that follow." I disagree 100% with his opinion that an active/dynamic "kicking in motion of the right knee" is a very important biomechanical element at the start of the backswing, and I regard it as an acceptable personal choice, that should not be deemed to be mandatory. Brandel Chamblee provided no sound explanatory reasoning to bolster his personal choice of an active/dynamic "kicking in motion of the right knee" at the start of the backswing, and I believe that each individual golfer should personally decide whether it offers him any benefit. I believe that it is an idiosyncratic personal choice - like choosing whether or not to waggle the club just prior to initiating the takeaway.

Brandel Chamblee also believes that a golfer should setup with his right knee statically angled inwards at address, and he uses Ben Hogan as an example. Here are the comments that Brandel Chamblee made in his book [1] regarding Ben Hogan-: "One of the more interesting changes to Ben Hogan’s setup through the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, as he changed his swing to turn himself from a hooker to a fader, was the degree to which he inclined his right knee toward the target at address to use it as a trigger to begin the takeaway. This subtle change had profound effects with regard to the firing of his right leg in the downswing, specifically that he was able to “unweight” the right foot, which is to say his right heel came off the ground as the club approached hip high, and this contributed to the proper sequencing of the unwinding of his body and, I don’t believe coincidentally, greater success with each passing decade." I have no objection to Ben Hogan's personal choice to statically incline his right knee slightly inwards at address, but I think that Brandel Chamblee's explanatory biomechanical reasoning is irrational. Brandel Chamblee claims that it enabled Ben Hogan to better "fire" his right leg in the early downswing and that it helped him to properly sequence the subsequent unwinding of his body. I personally do not believe that Ben Hogan actively "fired" his right leg and "unweighted" his right foot in order to start the downswing's kinematic sequence with a pelvic rotary motion (which Ben Hogan called a "left hip clearing" type of pelvic motion) and I believe that Ben Hogan started his downswing's pelvic rotary motion by *activating his right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles that caused his pelvis to rotate counterclockwise away from his weight-pressure loaded right leg/foot while simultaneously activating his left-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles in order to externally rotate his left femur in his left hip joint thereby ensuring that he could achieve a state of dual-external rotation of his two femurs at the P5 position.

(* I have described the biomechanics of an optimal pelvic rotary motion in great detail in my review paper called "Critical Update: How to Optimally Rotate the Pelvis During the Downswing")

Brandel Chamblee also argued in his book [1] that actively "kicking in" the right knee and elevating the right heel helps a golfer to straighten the left leg and elevate the left side of the pelvis in the later downswing, but I don't understand the unexplained nature of the biomechanics that could possibly undergird his proposed/theoretical causal connection. I believe that the *left leg straightens, and that the *left side of the pelvis elevates, in the mid-late downswing due to the muscular activation of the left knee extensor muscles in the anterior compartment of the left thigh and due to activation of the left gluteus maximus muscle and I believe that they are being activated while the golfer (who is a front-foot golfer) is increasingly weight-pressure loading, and thereby bracing, his left leg. I do not believe that i) any kicking in motion of the right knee and ii) any lifting of the right heel motion plays any role in this left-sided swing action.

(* I have described the biomechanics of this biomechanical phenomenon in great detail in my review paper called "Critical Update: How to Optimally Rotate the Pelvis During the Downswing")

Brandel Chamblee provided another line of reasoning to bolster his recommendation that a golfer should incline his right knee inwards at address, and he stated in his book [1]-: "That both Hogan and Nicklaus wrote about this often-overlooked key is no surprise, given that both great players are linked through a lineage of influences that traces its way back to Alex Morrison, (we already know) who wrote at great length about the need to start the swing with the right knee kicked in to initiate the motion of the swing. Morrison believed that kicking the right knee in as little as two inches at address would compensate for a slight lateral shift— a corresponding two inches— off the ball without the weight tipping over to the outside of the right foot. The weight shift would lead to a low takeaway, giving width to the swing, while also giving the player a brace to start the downswing. All of this would be achieved by the simple act of feeling a little pressure on the inside part of the right foot to begin the backswing, something we see far too little of in professional golf today, where many look like their lower bodies have been carved in stone prior to initiating the takeaway." This line of reasoning makes more sense to me, because having the right knee slightly kicked-in at address, and therefore at the start of the backswing, may help a golfer to better brace the right leg/knee during the backswing and it may thereby help (if it is associated with increased weight-pressure loading of the right leg/foot) the golfer to prevent lateral swaying of the pelvis (or right upper thigh) away from the target during the backswing action, and it also helps to prevent transfer of weight-pressure too far to the outside of the right foot. I therefore would also encourage golfers to consider the advisability of adopting Ben Hogan's reverse-K look (which involves a small degree of right knee inwards-inclination) at address as an optional choice - as depicted in the following artist-drawn image of a reverse-K address posture.

Image copied from reference number [2]

That image shows that the right knee is definitely inwards-inclined at address,

and I think that it is a perfectly acceptable address position.

However, I think that it it is also perfectly acceptable to stand with the knees more symmetrically aligned at address - as seen in this next image of Nick Faldo at address.

Image copied from reference number [3]

Nick Faldo's knees look more symmetrically aligned at address, but that doesn't

prevent him from weight-pressure loading and bracing his right leg/knee in an

optimal manner during his backswing action, and I do not perceive that he is standing as if his

lower body has been "carved in stone" at the initiation of his takeaway.

Consider Jordan Spieth (image 1) and Jason Day (image 2) at address when swinging a driver.

Capture images derived from swing videos

Note that both golfers do not have their right knee

inwards-inclined at address. Brandel Chamblee may perceive their lower body as

being "carved in stone" at the start of their takeaway, but I think that they

have a perfectly acceptable address posture at the start of their takeaway. I

think that having both knees symmetrically facing slightly outwards at address

is an optional choice, which can work just as well as the alternative optional choice of having one's

right knee statically inclined inwards at address. I think that

each individual golfer should feel free to experiment in order to decide which

optional choice works best for him.

Ball position

In his book [1] Brandel Chamblee stated that the SLAP authors [2] noted that most professional golfers position their ball well forward in their stance with no more than 3" between the position of the ball when using a driver relative to their ball position when using a short iron (where the ball is still positioned ahead of the middle of the stance). Brandel Chamblee states that it encourages a better forward motion of the body during the downswing (without having to move the head and body ahead of the ball by impact) and an optimum clubhead path. I agree with Brandel Chamblee regarding his opinions on the optimum ball position.

Chapter 3 - Posture

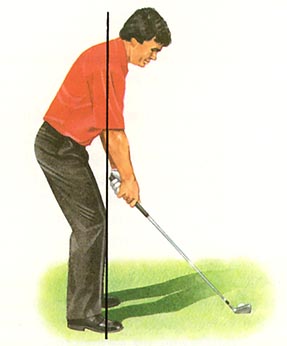

Brandel Chamblee states that the knees should be slightly bent at address so that the knees are directly over the shoelaces. I agree with his opinion and I think that a line drawn vertically downwards from directly in front of the knee cap should strike the ground approximately between the forefoot and midfoot (as demonstrated in the following image).

Image copied from reference number [4]

Note that the vertical black line passes just in front of the shoelaces, which means that the knees are positioned over the shoelaces. I think that the most important issue is that the knees should "feel" lively and that the golfer's weight should be equally be distributed over the forefoot relative to the hindfoot. A golfer should not "feel" that he is falling forward over his toes, or backwards towards his heels, at address.

Regarding spinal posture, Brandel Chamblee stated in his book [1] -: "If there is one area that has the most commonality among those who won the biggest events in golf, it is in the neutral or slightly concave position of the lower back and the curved position of the upper back at address. This is what they did." It may be true that those "great golfers who won the biggest events" manifested Brandel Chamblee's "desired" spinal posture, but so did most of their fellow competitors, who did not win any competitions. I think that's a very weak way of arguing on behalf of the "supposed" merits of any particular spinal posture. I think that a golfer should consider Brandel Chamblee's recommended type of spinal posture as being meritorious because it can be shown to be biomechanically natural/comfortable.

Consider the following image of Nick Faldo.

Image copied from reference number [3]

Note that I have altered that copied image by superimposing an image of the

spine over Nick Faldo's image (using Photoshop). Note that the human spine

normally/naturally has a small degree of lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis

when a person stands erect, and I believe that it is natural and biomechanically

comfortable for a professional golfer to maintain that same spinal posture when

bending over at the level of the hip joints (and not at the level of the waist)

when he adopts his desired spinal bend inclination angle.

Brandel Chamblee is rigidly opposed to any straightening of the thoracic spine, and he wrote in his book [1]-: "Keeping the upper back straight and not rounded at address is a common point of modern instruction, and a glance up and down any range at a Tour event will show player after player with ramrod-straight backs. This might be aesthetically appealing, but I believe it’s a case of overcorrection, also known as hypercorrection. When trying to keep the upper part of the back straight, very often the lower part of the back becomes excessively concave. This tug of war to pull the spine straight creates far too much tension and makes it nearly impossible to get the fluidity that one seeks at the start of the backswing to say nothing of the truncating effect it has later in the swing." I agree with Brandel Chamblee that adopting a ramrod straight upper back at address may potentially create too much tension, but I do not think that a non-stiff straightening of the upper back (as manifested by many tour professional golfers) creates any unnatural tension that will hamper their swing action.

Consider the straightening of the upper back seen in these four PGA tour professional golfers.

Image 1 = Charles Schwartzel; image 2 = Adam Scott; image 3 = Jason Day and

image 4 = Michelle Wie.

I copied the images of Charles Schwartzel and Adam Scott from Brandel Chamblee's book [1] because he used them as examples of golfers whose backs are too straight (from his personal perspective), and I have added another two examples (Jason Day and Michele Wie) who have the same "straight back" look. I personally do not believe that they have ramrod straight backs, which is associated with an inordinate amount of muscular tension, and I regard their spinal posture as being perfectly acceptable because I think that it is perfectly natural/comfortable for them to acquire their "straight back" posture without any unnatural tension. From my personal perspective, I am only opposed to a ramrod straight back address posture that is "artificially" dependent on an excessive amount of muscular tension.

Distance from the ball

Brandel Chamblee states in his book [1]-: "Jack Nicklaus said that in taking his setup if an imaginary line were drawn from the top of his shoulders to the ball the left arm and club would dip slightly beneath this line and he liked to have a slight bend at the elbows. Almost every great player has had this look, where their hands hang just outside of a vertical line straight down from their shoulders, a look of freedom and comfort."

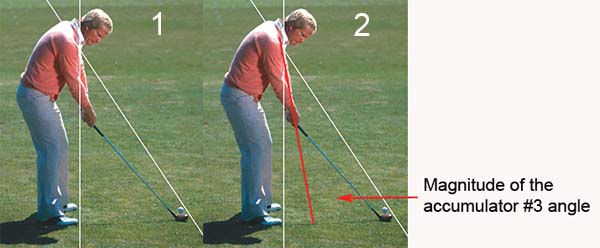

Here is a copy of the Jack Nicklaus image from Brandel Chamblee's book [1].

Image 1 is an unedited copy of the image of Jack Nicklaus from Brandel

Chamblee's book [1].

Jack Nicklaus has the typical "hand distance from the body" posture of a golfer who uses a low palmar left hand grip. In image 2, I have drawn a straight red line down the length of his left arm (and that red line strikes the ground closer to his feet than the ball-target line) and one can clearly see that he has a moderate-sized accumulator #3 angle.

I believe that the size of the accumulator #3 angle is very dependent on whether one uses a mid-palmar grip (like Bryson DeChambeau and Moe Norman) or a low palmar grip (like Jack Nicklaus) and the left hand grip pattern has a major effect on the distance of the hands from the body at address - presuming that one has a neutral left wrist (in the plane of radial => ulnar deviation) at address and that one doesn't have a marked "artificial" tendency to radially or ulnarly deviate the left wrist to an inordinate degree at address.

Brandel Chamblee made the following comments in his book [1]-: "I will say though that I think history has favored those who stand closer to the ball and I don’t think it is a coincidence. Those who stretched a little to get to the ball were some of the great practicers of all time, men such as Ben Hogan, Gary Player, Lee Trevino, and the cultish figure of Canadian Moe Norman. Standing farther from the ball means that the club cuts more to the inside on the takeaway and comes into the ball on a shallower angle. This shallower plane line means the clubhead will feel heavier mid-backswing and this sense of added weight can cause a responsive tensing of the hands, which one could argue disrupts the flow of the swing and requires more effort and practice to overcome. This is perhaps one of the reasons why flat swingers tend to be quicker and upright swings are more rhythmical." It is obvious that having a small accumulator #3 angle (due to adopting a mid-palmar left hand grip) means that there is small angle between the left arm and the clubshaft at address and impact, but it doesn't mean that the clubshaft travels on a shallower plane, or that there is a responsive tensing of the hands, or that the swing action doesn't flow in a more rhythmical manner. I think that Brandel Chamblee's explanation is totally meritless, and I suspect that he doesn't understand how different left hand grip patterns affect the accumulator #3 angle at address and at impact.

Consider Bryson DeChambeau's golf swing action - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bvdY2HA9g08

Here are capture images from his swing video.

Image 1 shows Bryson DeChambeau at address. I have drawn a red line down the

length of his left arm, and that red line strikes the ground much closer to the

ball-target line - compared to the image of Jack Nicklaus at address (see the

image just above this image) - which indicates that his left arm is more

outstretched.

However, that doesn't mean that his clubshaft "cuts more to the inside during his takeaway" as Brandel Chamblee wrongly asserts - note how steep his clubshaft is at the P3 position (image 2) when it lies on the same plane as it lay at address (which is just below the TSP). Brandel Chamblee is seemingly oblivious of the "effect" that the pattern of left hand grip (mid-palmar grip pattern versus low palmar grip pattern) has on the "degree of steepness" the clubshaft will angle upwards during the backswing's left wrist upcocking action.

Image 3 shows Bryson DeChambeau at his end-backswing position with his clubshaft just below the TSP. Image 4 shows that he has a zero-plane shift action during his early-mid downswing - note that his clubshaft descends down the same plane to impact (image 5) and it doesn't come down a shallower plane.

I also think that Brandel Chamblee's "belief" that going up, and coming down, a shallower plane - as seen in Ben Hogan's and Matt Kuchar's and Rickie Fowler's backswing and downswing - causes hand tension and/or a non-rhythmical flow of the swing has no biomechanical validity.

Finally, Brandel Chamblee made the following comment about Byron Nelson in his book [1]-: "Given the benefits of standing a little closer to the ball, it is no surprise that fairly early in his career, once his swing became grooved, Byron Nelson said he could go three weeks without touching a club and it wouldn’t affect him at all. Famously during his streak of eleven wins in a row in 1945 it was said that his pre-round warmups were never more than a half dozen or a dozen shots."

I think that's a very weak argument! I could imagine that Moe Norman, who also had a very grooved swing (but whose arms were very outstretched at address), could also go "three weeks without touching a club and it wouldn't affect him at all" - although it is difficult to imagine the late Moe Norman not wanting to touch a golf club for a three week time period, considering the "fact" that he loved to swing his golf club on a daily basis.

Alignment

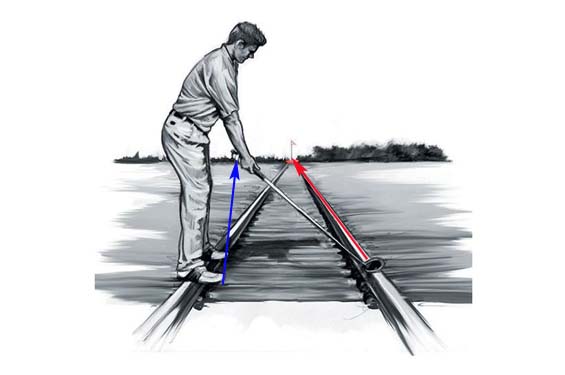

Brandel Chamblee made the following opening comment in the "alignment sub-section" of his book [1]-: "Perhaps one of the biggest misunderstandings about touring professionals is that they set up square to their target. This idea fits nicely with the railroad track analogy that is given, I’m sure out of convenience, to illustrate that the feet should be placed in such a manner that if a line were drawn across the toes it would be parallel to the target line, with the two imaginary lines extending off into the distance, resembling train tracks. If taken as true and applied to every club in the bag, you will likely be setting up to fail. ---- Thanks to the diagnostic equipment we have today we know that most professional golfers hit down on the ball with every club in the bag, if only slightly with the driver. I say “most” because there are a few who hit up on their drivers. As mentioned in the last chapter we know further that if the club is descending or going down, its path is going to the right of the target line. This is why most professional golfers set up with their feet open, or to the left of their target line, offsetting with the alignment of their feet the path of the club."

I think that Brandel Chamblee is wrong about his two claims - i) Claim number 1 - that most professional golfers set up with an open stance and ii) claim number 2 - that they do so because they need to offset an "in-to-out" clubhead path with an open alignment of the feet.

First of all, the degree of "in-to-out" clubhead path at impact is very small when a golfer hits his driver, fairway woods or long irons because the downward clubhead attack angle at impact is very small and only in the range of 0.5 - 2 degrees. Secondly, a skilled professional golfer could easily adjust his clubhead path by altering the angle that his left arm/clubshaft descend down to impact (relative to his body) in order to accomodate for such a small 0.5 - 2 degrees downward clubhead attack angle - without having to adopt an open stance. Thirdly, it is my distinct impression that many professional golfers only have an overtly open stance at address when hitting short irons, and I suspect that most professional golfers adopt a square stance at address when hitting longer irons or a driver.

Consider this image that Brandel Chamblee used in his book [1] to demonstrate an open stance.

Copy of an image from Brandel Chamblee's book [1]

Note that the artist drew the feet slightly open relative to the left railroad

track - thereby implying that the foot stance is open relative to the

ball-target line.

However, Brandel Chamblee seemingly made the fundamental mistake of instructing the artist to draw the flag (target) midway between the feet and the clubhead!

Here is an edited image of the above image.

Edited image of an image that I copied from Brandel Chamblee's book [1]

I have drawn a red arrowed line between the clubhead and the flag (target) and

that line represents the ball-target line. I have drawn a blue arrowed line

across the front of both feet. Note that the blue line is closed,

and not open, relative to the red line.

I believe that the above image misrepresents "reality, and I believe that the following image better represents "reality".

Image copied from reference number [5]

Note that the flag (target) is situated "straight-in-line" with the golfer's

clubhead, and that the yellow line drawn between his clubhead and the target

represents his ball-target line (which is parallel to the 1st golf club that is

lying on the ground). If the golfer's clubface is square relative to the yellow

line, then his clubface must be facing the target (represented by point X).

Note that the golfer's foot stance is parallel to the ball-target line and also parallel to the 2nd golf club (which is closer to his feet) and that both golf clubs are parallel relative to each other. Note that I have drawn a second yellow line in front of his feet to accurately represent his foot stance alignment and that second yellow line points at point Y, which is well left of the target. Note that both knees, both thighs, both hip joints and both shoulders are parallel to the second yellow line, which points at point Y. To the uninitiated golfer, who hasn't thought deeply about the issue of "alignment", he may get the impression that the golfer is aligned open relative to the ball-target line, but's that a wrong impression! The golfer is obviously aligning his feet/body square (parallel) relative to the ball-target line, and point Y must be well left of point X under those conditions. The absolute distance (in feet) between point X and point Y will obviously become progressively greater the further the flag (target) is from the golfer - but that doesn't mean that the golfer's alignment is open! I would recommend that you keep this important "fact" in mind when watching professional golfers on TV - when the camera is positioned down-the-line (DTL) relative to the golfer.

Spine Angle

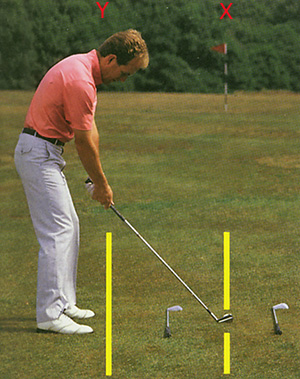

Brandel Chamblee posted the following composite image in his book [1]

Brandel Chamblee claimed that Byron Nelson, Sam Snead and Cary Middlecoff all

had a reverse-K position setup at address where the right side is lower than the

left side and where the golfer has rightwards spinal tilt. I agree with Brandel

Chamblee that having a small degree of rightwards spinal tilt is a very suitable

spine angle at address. However, I don't agree that it is necessary to have the

right knee kicked-in at address in order to achieve that goal. There are two

ways to get rightwards spinal tilt at address. Method 1 - one

could kick-in the right knee and move the pelvis slightly targetwards so that

the pelvis is closer to to the left foot, rather than being centered between the

feet at address. That would move the lower lumbar spine targetwards and promote

rightwards spinal tilt if the head is kept stationary. Cary Middlecoff (3rd

image) is apparently using that method. Method 2 -

alternatively, one could have a more symmetrical knee position with the pelvis

more centered between the feet, but one could angle the upper torso slightly

rightwards in order to achieve a small degree of rightwards spinal tilt. Bryson

Nelson (1st image) has that "look" in the above composite image even though he "supposedly" had a reverse-K

setup with his right knee kicked-in (according to Brandel Chamblee).

Consider Jordan Spieth and Jason Day at address.

Note that they have an appropriate amount of rightwards spinal tilt - even

though they have not kicked-in the right knee.

I believe that both methods of acquiring rightwards spinal tilt at address are biomechanically acceptable.

The position of the head

Brandel Chamblee starts off with the following comment in this subsection of his book [1]-: "Almost a hundred years ago, Alex Morrison in his book A New Way to Better Golf on page 49 stated that: “You must point your chin at a spot just back of the ball and keep it pointed there until well after the ball has been hit.” He went on to say that pointing one’s chin behind the ball at address and throughout the swing was the most important single element in the correct swing and that it was not based on idiosyncrasies but on the anatomical structure of the human body. ----- Bobby Jones, having read Alex Morrison’s teachings, said, “I am convinced that this is sound, for it places the head in a position where it will not tie up the rest of the body, either on the backswing or in the act of hitting the ball.” This positioning was patently visible in Bobby Jones as he turned his head to the right as he started his backswing, almost as a trigger, and he kept it pointed well behind the ball until after impact. As did Byron Nelson, Ben Hogan, Sam Snead, and Jack Nicklaus. Jack turned his head to the right because he said Snead did it and if it was good enough for Snead it was good enough for him."

I think that Alex Morrison's comment that pointing one's chin at a spot behind the ball and keeping it pointed there until after impact is not based on the anatomical structure of the body (as he wrongheadedly claims). The true anatomical reality is that the head is exterior to the torso, and it is suspended above the rotating/pivoting torso via a very flexible cervical spine and a very rotatable atlanto-occipital joint that allows the head to easily move independently of the torso. That means that the golfer can freely decide whether to rotate the head away from the target during the backswing (which Brandel Chamblee favors) or whether to keep his head stationary. Also, he can then freely decide whether to keep his head stationary (with his chin pointing behind the ball) during his downswing and early followthrough action (which Brandel Chamblee favors) or he can swivel his head targetwards at the level of his atlanto-occipital joint (like Annika Sorenstam and David Duval). I think that all these different options are biomechanically acceptable.

Brandel Chamblee stated that Jack Nicklaus swiveled his

head slightly away from the target during his early backswing because "he

said Snead did it and if it was good enough for Snead it was good enough for

him." I think that's a very biomechanically unsound way of justifying one's

personal choice of a biomechanical swing element. Brandel Chamblee provides

another biomechanical reason in his book [1] when he states-: "This position

of the head allowed for a bigger turn of the upper body and kept passive in

transition, if only for an instant, the right side of the body and allowed the

proper sequencing of the downswing." I believe that there is zero merit to

Brandel Chamblee's biomechanical reasoning. First of all, turning one's

head/chin slightly to the right during the backswing (like Jack Nicklaus)

doesn't necessarily allow for a greater degree of upper torso rotation

if the golfer has a very flexible cervical spine, and it may only make

a significant difference in a senior golfer who has an inflexible cervical

spine. Therefore, it should be considered to be an optional swing element

choice, and not a mandatory swing element choice. Secondly, I cannot envisage

how keeping the head swiveled slightly away from the target at the start of the

transition to the downswing causes "a proper sequencing of the downswing".

The following comments in his book [1] represents Brandel Chamblee's

biomechanical explanation-: "The left side begins its target-ward move and

stretches and the right shoulder, if only for a fraction of a second, is held

back. In that fraction of a second the right shoulder drops, something I will

discuss later in this book, setting the body up for an inside to down the line

attack at the ball. This position of the head facilitates the stretch in the

shoulders in transition and adds width to the downswing." I believe that

Brandel Chamblee's biomechanical cause-and-effect reasoning - when he infers

that keeping the chin pointing behind the ball facilitates the stretch of the

shoulders and adds width to the downswing - is irrational.

Brandel Chamblee is so enamored of the idea of a golfer keeping his chin

pointing well behind the ball during the downswing that he wrote-: "In the

mid-1990s I saw sequence photos of Tiger Woods’s golf swing and in them he had

the almost identical head position of the great players. As the club approached

waist high on the downswing, his chin was still pointed well behind the ball,

the picture capturing perfectly a position common to the greatest players of all

time. I remember thinking, there is no stopping this young man." I think

that Brandel Chamblee's argument is very weak when he states that "there was

no stopping this young man" simply because Tiger Woods manifested

this single swing element that he particularly favors. What about Annika

Sorenstam who is regarded as one of the greatest female golfers in the history

of golf? Annika Sorenstam swiveled her head targetwards (in an idiosyncratic

manner) during her downswing and it didn't harm her downswing action! Why should it?

The "reality" is that both swing element options (keeping the head stationary

with the chin pointing behind the ball and swiveling the head targetwards at the

level of the atlanto-occipital joint) are

biomechanically acceptable during the downswing - because of the evolved nature

of human anatomy where the head can very easily move independently of the

rotating torso due to the existence of a very flexible cervical spine and a very

rotatable atlanto-occipital joint.

Chapter 4 - Triggering the Swing

This represents Brandel Chamblee's opinion regarding a triggering motion

at the start of the backswing action, when he wrote in his book[1]-: "Almost

without exception, going back to the earliest days of this game, the best

professional golfers have written about the importance of the movement of the

body that precedes the swing, to stave off tension. Some have waggled the club,

like Ben Hogan, who famously wrote on the subject, while others like Bobby Jones

and Lee Trevino took a few steps as they addressed the ball to kick-start their

swings. Still others like Gary Player and Mickey Wright talked of using a

forward press to initiate, as much by rebound, the beginning of the backswing.

Jack Nicklaus and Sam Snead both used a combination of the forward press of

their bodies, though it was more pronounced in Sam, and a turning of their heads

to the right to serve as a preamble to their move away from the ball.

Perhaps one of the most ruinous trends in professional and amateur golf alike is

the death of what Hogan called “the bridge” between the setup and the backswing.

As the game’s teaching has become more and more complex and microscopic in

nature, players of all abilities have become frozen in thought over the ball

and, it seems, have lost sight of the fact that the goal is to move in as big a

circle as possible, as fast as possible, as smoothly as possible— and none of

those three things can be accomplished as easily without being relaxed as the

swing begins."

I think that Brandel Chamblee's presumptious "belief" that a golfer must automatically be non-relaxed at the start of the backswing if he doesn't use a triggering motion as a "bridge" between the setup and the backswing has no scientific/biomechanical validity. Many golfers have no difficulty starting the backswing in a relaxed manner, without feeling that they are "frozen in thought over the ball", even though no they do not use a preliminary triggering motion. If a golfer performs the backswing in a more relaxed manner by first using a triggering motion, then that's a perfectly acceptable choice from my perspective, but I do not believe that a triggering motion should be deemed to be a mandatory requirement for all golfers.

Chapter 5 - The Initial Move Away From the Ball.

Brandel Chamblee prefers an one-piece takeaway where the trinity of the

shoulders, arms and hands move together as "one-piece" and where the clubhead is

kept low to the ground during the initial takeaway. I have no objection to his

general description of the one-piece takeaway, although I do not agree with his

"belief" in the value of a lagging takeaway where there is a

"feeling" of moving the hands backwards away from the target while allowing the

clubhead's backwards-motion to be momentarily delayed (which will cause a

fractional increase in the degree of left wrist bending) at the very start of

the backswing action.

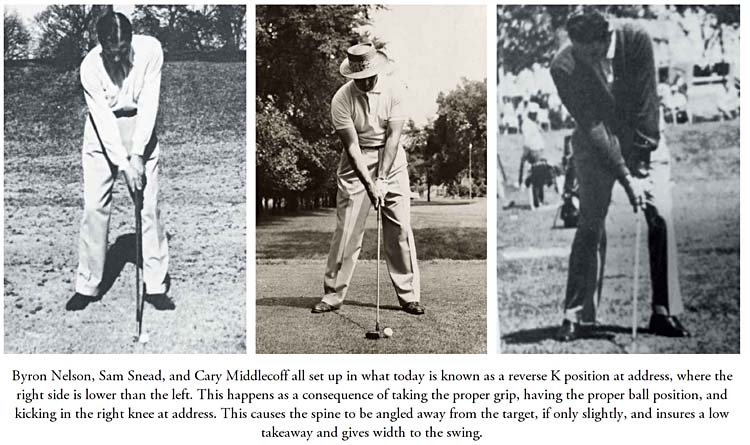

Brandel Chamblee used this composite capture image of Sam Snead to portray the lagging takeaway.

Image copied from an image in reference number [1]

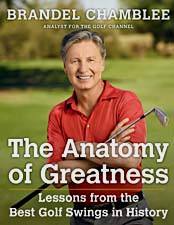

Brandel Chamblee commented as follows with respect to Sam Snead's takeaway

action-: "Sam Snead, with no sign of setting his wrists in his initial move

off the ball— indeed there is a hint of him leaving the clubhead behind— sets

the club on a low, wide takeaway. If this is done properly, as so many of the

greats did, there is no need to ever have to think of the path of the club at

any point on the backswing or downswing." I cannot understand how Brandel

Chamblee can rationally argue that if a golfer makes a low, wide takeaway, that

"there is no need to ever have to think of the club at any point on the

backswing or downswing". The "idea" that performing an optimum takeaway

(whatever that means) between P1 and P2 will mean that a golfer doesn't ever

have to think of his club during the remainder of the backswing (between P2 and

P4) or at any time point during the downswing (between P4 and impact) is an

oversimplistic "idea" that I find astonishing.

Note that Brandel Chamblee used the phrase "a hint of leaving the clubhead behind". What does he mean by that written description?

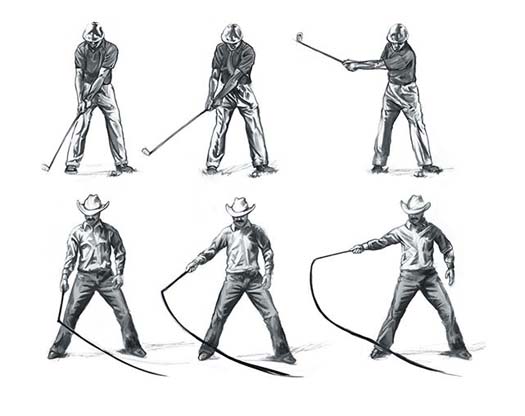

Brandel Chamblee offers this artist-drawn image of a person preparing to crack a whip as an analogy.

Image copied from an image in reference number [1]

In his book [1], Brandel Chamblee commented as follows regarding the above image

image-: "THE INITIAL MOVE AWAY FROM THE BALL can be likened, to some degree,

to the initial move when one is cracking a whip, where the hand moves in the

loading direction and precedes the tip of the whip. It is this feeling that one

should have to execute the movement of the loading of the club and setting it on

the right path." I can personally discern no rational reason to use this

type of lagging takeaway action, and I much prefer a takeaway action where one

creates an intact LAFW alignment as soon as possible between P1 and P1.5 - as

demonstrated by Martin Hall in one of his golf instructional videos.

Here are capture images from a Martin Hall golf

instructional video at

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=44fev4wqC6U (which unfortunately is no longer

publically available online because of a copyright claim made by the Golf

Channel).

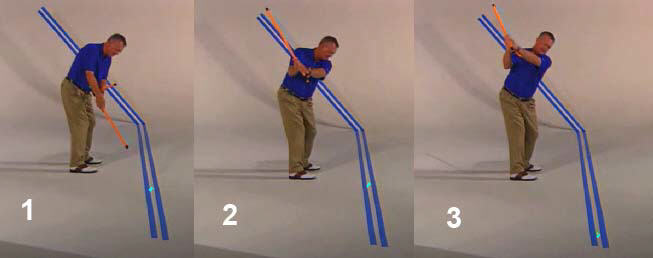

Martin Hall demonstrating the start of the takeaway

action

Note that Martin Hall has placed a door hinge on the back (dorsum) of his right wrist - and that hinge is placed there to emphasize the fact that the right wrist should only hinge back (dorsiflex), and not upcock (radially deviate) during the early backswing. He has also placed a door hinge on the radial side of his left wrist - and that hinge is placed there to emphasize the fact that the left wrist should only cock upwards (radially deviate) in the backswing (and never bend backwards in the plane of left wrist flexion-extension).

Image 1 shows Martin Hall at address. Note that the left wrist is significantly cupped (green angled line). The degree of cupping is greater than the amount of cupping that would exist if a golfer, who has a neutral left hand grip, had a GFLW (where the clubshaft and left arm are in a straight line alignment) at address - because the left wrist is slightly bent due to the fact that the clubshaft and left arm are not in a straight line relationship because Martin Hall prefers to hold the clubshaft roughly perpendicular to the ball-target line at address. Note that the right wrist is nearly flat (yellow anglde line).

Note what happens at the start of the takeaway - image 2. The right wrist starts to bend backwards and this biomechanical action causes the left arm and clubshaft to become aligned in a straight line relationship - and that straight line relationship constitutes an intact LAFW. Note that the bend in the left wrist disappears and a GFLW is established. From this point onwards, Martin Hall shows how a golfer should start to roll the intact LAFW (and his GFLW) onto the inclined plane. Image 3 shows Martin Hall at the end-takeaway position. Note that his left lower forearm (watchface area) and GFLW has rotated ~90 degrees from its address position and that the back of the GFLW is now roughly parallel to the ball-target line. Note that his right wrist has bent back (yellow angled line) more than it was at address.

I believe that creating an intact LAFW/GFLW alignment during the P1 => P2 time period is the optimum way to perform a takeaway action - whether one uses the one-piece takeaway action or a right forearm takeaway (RFT) action - and I will have much more to say about this "intact LAFW/GFLW" topic in the next subsection of this review paper.

Chapter 6 - The Completion of the Backswing

There are many issues to discuss in this subsection of my book

review paper, because I disagree with many of Brandel Chamblee's written

opinions as expressed in chapter 6 of his book [1].

Width

Brandel Chamblee is not only in favor of the one-piece takeaway, he is also in favor of a very wide clubhead arc during the backswing's one-piece takeaway action. Brandel Chamblee believes that a golfer should keep the clubhead as far away from the body as possible during the *P2 to P3 time period, which he believes will correlate with increased swing power. He is seemingly against the idea of setting the wrists early because he believes that it will result in a narrower clubhead arc and thereby rob a golfer of potential swing power.

(* see this review paper if you do not understand the P system of classifying a golfer's position during the full golf swing)

I believe that Brandel Chamblee is wrong because I do not believe that there is any reason to believe that there is a direct causal connection between the width of the clubhead arc during the backswing and a golfer's potential swing power. I also believe that an earlier setting of the wrists does not significantly narrow the backswing's left hand arc path, which I think is a better measure of backswing width.

Consider my argument.

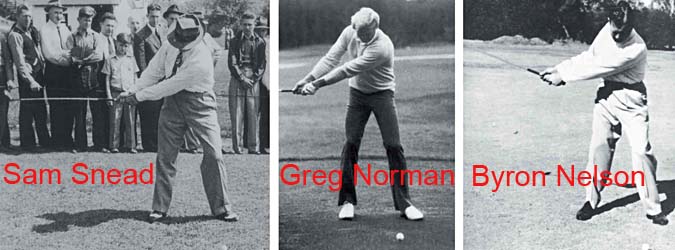

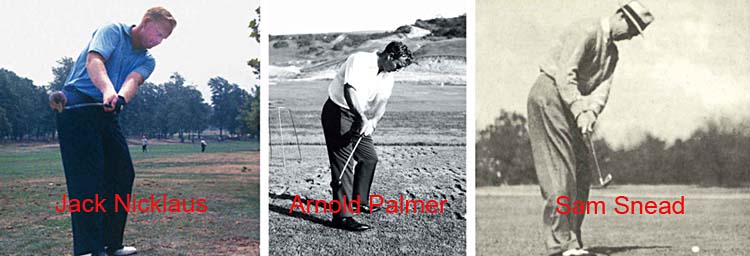

Here is a copy of a composite image from Brandel Chamblee's book [1] featuring three professional golfers who use an one-piece takeaway, and who do not have an *early setting of the wrists.

(* the term "early setting of the wrists" is often used to refer to the biomechanical phenomenon of an early left wrist upcocking action).

Edited copy of an image from reference number [1]

Note that all three golfers - Sam Snead, Greg Norman

and Byron Nelson - are using an one-piece takeaway while avoiding an early left

wrist setting action. Note that all three golfers are using a

rightwards-centralised backswing action and that they are all rotating their

upper torso (shoulders) perpendicularly around their rightwards tilted spine. Note that they all

have a straight left arm. In particular, note that they all have very little

bend in the right elbow, which is a characteristic biomechanical feature of an

one-piece takeaway action.

I personally have no objection to the use of an one-piece takeaway action, even though I personally prefer a *right forearm takeaway (RFT) action.

(* I have described the biomechanics of the RFT action in great detail in my backswing chapter)

I have previously used Stuart Appleby's backswing action as a prototypical example of a RFT pattern of takeaway action, and here is the composite image of Stuart Appleby's backswing action, which I previously used in my description of a RFT action.

I have red-highlighted Stuart Appleby's right arm/hand, so that one can pay

particular attention to two characteristic biomechanical features of the RFT -

which is an earlier bending back of the right wrist (see image 2) and an earlier

bending of the right elbow (see image 3). Those two biomechanical features are

causally associated with an earlier setting of the wrists (left wrist upcocking

action).

To better compare Stuart Appleby to the three golfers (Sam Snead, Greg Norman and Byron Nelson), I have captured an image of Stuart Appleby at a comparable P2.5 mid-backswing position.

I have captured a face-on image and DTL image of Stuart Appleby at his P2.5

position (mid-backswing position). Because his clubshaft is not clearly visible

in the face-on image, I have drawn a thin grey line over his clubshaft to better

show its position. Note that Stuart Appleby has slightly more right elbow bend

and a greater degree of setting of the wrists - compared to those three golfers

(Sam Snead, Greg Norman and Byron Nelson) at a comparable

position. Those two biomechanical facts obviously means that his clubhead

arc will be significantly narrower. However, his biomechanical arc ( = left hand

arc) is only fractionally narrower! The biomechanical arc is a

measure of how far the left hand has moved away from the target during the

backswing action, and it is determined by i) how far the left shoulder socket has moved

away from the target + ii) how straight the left arm is during that time period

and also how much it is angled inwards. Note that Stuart Appleby also uses a

rightwards-centralised backswing action and that he has roughly the same amount

of rightwards spinal tilt as those three golfers, which

means that his left shoulder socket has moved away from the target by roughly the same

amount (presuming a similar amount of upper torso rotation at a comparable P2.5

position). Note that Stuart Appleby also keeps his left arm straight, but it is

angled slightly more inwards (away from the ball-target line) due to his greater

degree of right elbow bending action and that will fractionally narrow

his overall biomechanical arc at that mid-backswing time point.

However, I believe that it doesn't really matter because his biomechanical arc

will end up being as equivalently wide as the biomechanical arc of those three

golfers (Sam Snead, Greg Norman and Byron Nelson) at the P3 - P4 position (see

image 5 above).

To better demonstrate my claim that the biomechanical arc of a golfer who uses the combination of a "RFT takeaway + early setting of the wrists" has approximately the same biomechanical arc width in the late backswing as a golfer who uses an one-piece takeaway (like Greg Norman), I will use as an example the backswing action of a golfer - Danny Willett (2016 Masters Champion) - who has a very exaggerated "early setting of the wrists" phenomenon during his RFT action.

Capture images (from a swing video) of Danny Willett's backswing action.

Image 1 shows that Danny Willett has a very early setting of his wrists (very

early left wrist upcocking action in the LAFW plane of radial deviation).

Image 2 is at the P2.5 position. Note that he has only a fractionally greater degree of right elbow bending than Stuart Appleby at a comparable position, which means that his biomechanical arc is fractionally narrower.

However, note how wide his biomechanical arc is at the P3 position (image 3).

To demonstrate that Danny Willett's biomechanical arc is as wide as Greg Norman's biomechanical arc at a comparable late backswing position, consider these capture images of Greg Norman's backswing action.

Image 1 shows that Greg Norman has a very wide clubhead arc, and a wide

biomechanical arc, at his P2.5 position and his biomechanical arc is obviously

wider than Danny Willett's biomechanical arc at a comparable position (see

image 2 above).

Image 2 shows Greg Norman at the P3 position. Note that he is now "setting his wrists", which requires a greater degree of bending of his right elbow.

Image 3 is a comparison image of Danny Willett at the same P3 position - note that his biomechanical arc is roughly similar in magnitude to Greg Norman's biomechanical arc and the difference is very small, and not really significant from a power accumulator #4 loading (left arm loading) perspective. The "fact" that Greg Norman's biomechanical arc is temporarily wider than Danny Willett's biomechanical arc between P2 and P2.5 is basically irrelevant because they both end up with a similarly wide biomechanical arc as they near their late backswing action between P3 and P4.

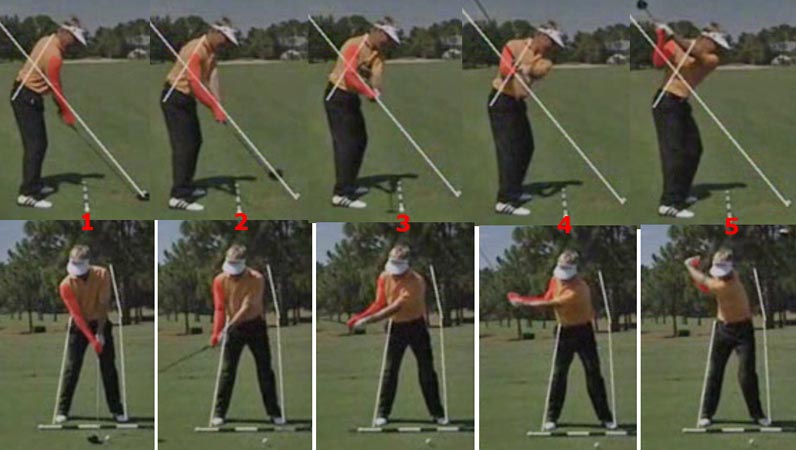

From a student-golfer's learning perspective, I think that if a student-golfer decides to use a RFT pattern of takeaway action (rather than the one-piece takeaway action), then he needs to ensure that he maintains the width of his biomechanical arc during the later backswing, which may require the incorporation of the TGM concept [6] known as "extensor action".

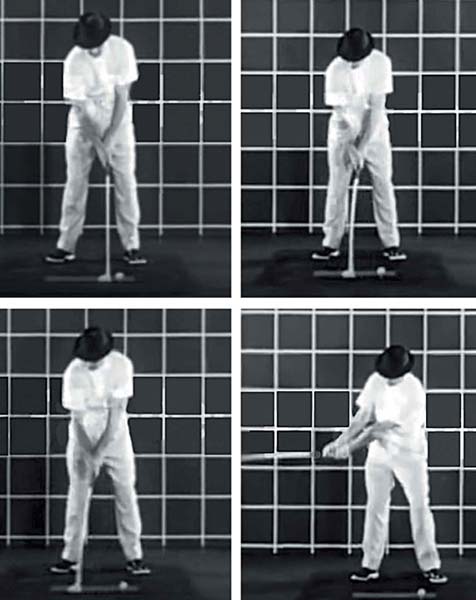

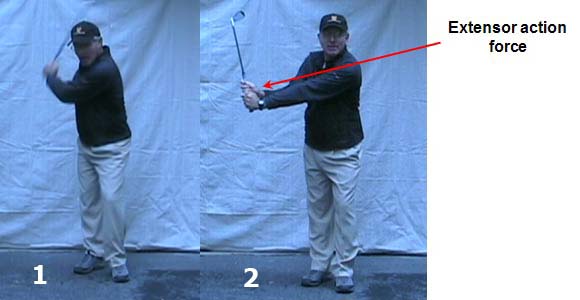

Here are capture images of the author (me) demonstrating the TGM concept [6] of "extensor action", which I described in great detail in my "How to Move the Arms, Wrists and Hands in The Golf Swing" review paper.

Image 1 shows the author performing a backswing action with his left arm alone.

Note the marked "bending of the left elbow" phenomenon that significantly

narrows the biomechanical arc. A student-golfer must avoid any

significant bending of the left elbow as this can significantly narrow the

biomechanical arc, which is a great disadvantage.

Image 2 shows the author using "extensor action" to help keep the left arm straight (comfortably straight, and not rigidly straight) during the entire backswing action. To apply an *extensor action force during a RFT action, a golfer must slightly extend the right elbow (even while it is bending as result of perfoming a RFT takeaway pattern of backswing action) so that the right palm can apply a small degree of push-force at PP#1 (which is located over the base of the dorsum of the left thumb) in a direction that is along the longitudinal axis of the left arm.

(* Interested readers can read this review paper if they want to better understand the biomechanics of an "extensor action" and I will not describe the complete details of this biomechanical action in this book review paper)

By the way, it is also important to realise that some golfers can very easily keep their left arm straight during their entire backswing action without applying an extensor action force, so an "extensor action" TGM-phenomenon should not be deemed to be an obligatory biomechanical phenomenon.

In summary, I believe that a golfer should optimally maximise the width of his biomechanical arc during his backswing action in order to ensure that he can maximise his swing power by loading power accumulator #4 in the optimal manner while simultaneously optimising his left arm's swing radius. However, in contrast to Brandel Chamblee, I believe that a golfer doesn't have to maximise the width of his clubhead arc in order to optimise the width of his biomechanical arc, and I believe that a golfer can generate a perfectly adequate biomechanical arc width using a RFT action combined with an early setting of the wrists (rather than an one-piece takeaway action combined with a late setting of the wrists). I would encourage each individual golfer to be open-minded about this issue, and to personally experiment, so that he can independently decide which type of takeaway action works best for him.

Clubface opening during the backswing

Brandel Chamblee not only favors the one-piece takeaway, he also favors the idea of a golfer resisting any tendency of the clubface to open during the backswing action secondary to a clockwise left forearm pronatory motion. Brandel Chamblee expressed the following comments in his book-: "As the left arm and club extend away from the target and the hands reach hip high, the right arm is above the left (if viewed from face on, the right arm is not obscured by the left) and has separated from the body. The right hand has pronated slightly (turned counterclockwise) and extended a bit (broken up toward the wrist), which puts the clubface in what has been called a shut position."

Although Brandel Chamblee focuses his mental attention on the right forearm/hand's degree of pronation in that description, I think that it is much more rational to focus one's mental attention on the degree of left forearm/hand rotary motion happening during the backswing's takeaway action - because I believe that most professional golfers are TGM swingers [6] who roll their intact LAFW onto the surface of their selected inclined plane (swingplane) by their mid-backswing.

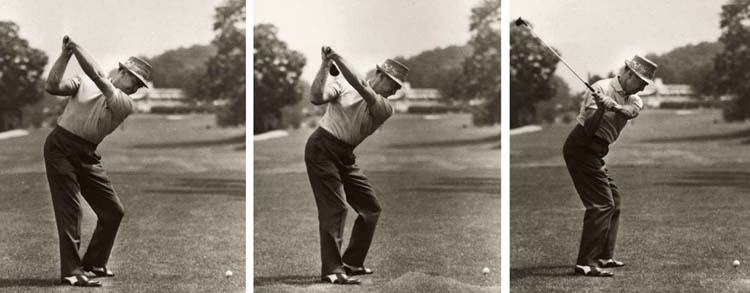

Here is a copied image from his book [1] showing what Brandel Chamblee calls a "shut face" (closed) clubface phenomenon during the early backswing.

Edited image copied from an image in reference number [1]

Brandel Chamblee made the following comments regarding this composite image of

Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer and Sam Snead in his book [1]-: "NOTICE THE

POSITION OF THE RIGHT HAND for Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer, and Sam Snead. At

this point in the swing it is facing slightly down to the ground in what is

known as a pronated position. This is contrary to the “toe up” principle or

rotating clockwise of the right hand thought that is so often espoused as

necessary to a correct backswing. As you will see, most athletic moves, in the

loading process, have the right hand (for a right hander) facing slightly to the

ground."

Note that Brandel Chamblee is opposed to the idea of the "toe-up" principle at the end-takeaway position (P2 position), which biomechanically requires a left forearm pronatory motion to happen that will cause the left hand (GFLW) to rotate clockwise by a finite amount during the P1 => P2 time period. Why does he oppose this biomechanical action and why does he prefer what he calls a "shut face" biomechanical motion during the takeaway?

Consider Brandel Chamblee's reasoning.

Brandel Chamblee wrote the following comments in his book [1]-: "The benefits of this shut position are immense as it keeps one from rolling the arms clockwise during the backswing— which you want to do during the transition (more on this move later)— but if you do it during the backswing you will likely be too open or laid off on the downswing, something Tour pros call “getting stuck,” and you will need to flip the hands to square the clubhead." Brandel Chamblee is stating that if a golfer rolls his arms clockwise during his backswing action - by the way, it is actually the left forearm which rolls clockwise because professional/skilled golfers do not really roll their left humerus more clockwise during their backswing action - that it will cause the clubface to be too open and/or "laid-off" during the early downswing, which he seemingly equates with a greater likelihood of the golfer "getting stuck" in the mid-downswing. I regard all of his opinions as being totally wrongheaded/meritless!

I will soon express a whole series of contrary opinions, which I will arbitrarily call "facts" because I believe that I can prove all the following "facts".

i) Fact number 1 - Most professional golfers roll their left forearm clockwise in a pronatory direction between the P1 position and the P3 position to a variable degree.

ii) Fact number 2 - The degree of pronatory roll of the left forearm happening between the P1 and P3 position is inversely proportional to the strength of the left hand grip.

iii) Fact number 3 - The "toe up" position at the end-takeaway position (P2 position) where the clubface becomes parallel to the ball-target line (due to a clockwise pronatory roll of the left forearm) only happens in golfers who have a weak/neutral left hand grip.

iv) Fact number 4 - Virtually all professional golfers will have the back of their left lower forearm (watchface area) parallel to their selected inclined plane (swingplane) by the P3 position if they have an intact LAFW and if their clubshaft is "on-plane".

v) Fact number 5 - All professional golfers who manifest a "shut face" phenomenon between P1 and P2 due to temporarily resisting any clockwise rotation of their left forearm during the takeaway time period will eventually perform a clockwise pronatory roll motion of their left forearm so that the back of their left lower forearm (watchface area) becomes parallel to their selected inclined plane (swingplane) by the P3 - P3.5 position if they have an intact LAFW and if their clubshaft is "on-plane".

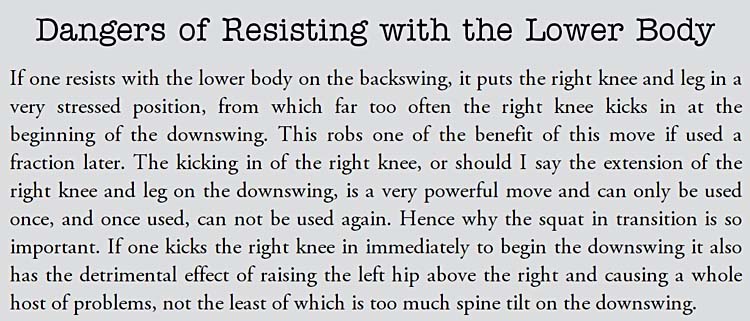

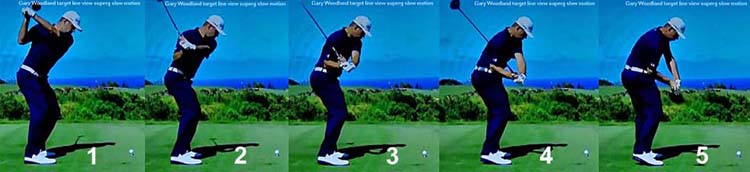

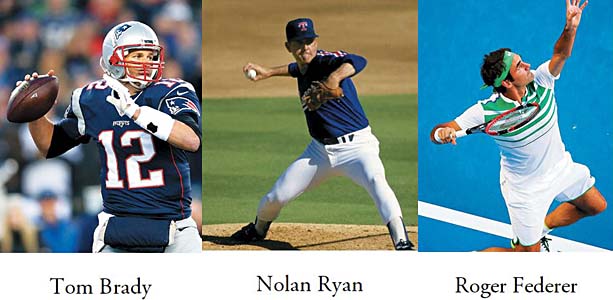

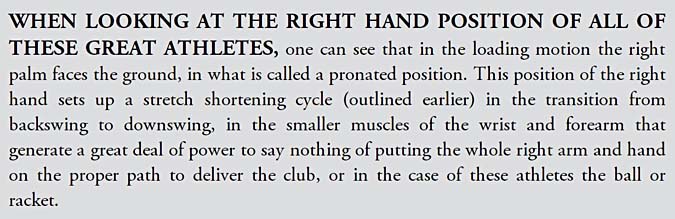

vi) Fact number 6 - The term being "laid off" is not causally connected to having an open clubface at the end-backswing position (due to having an appropriate amount of clockwise rotation of the left forearm happening during the backswing), but it is causally due to over-pronation of the left forearm happening during the P3.75 - P4 time period that causes the clubshaft to move "off-plane".